First: A criminal case

The British referred the matter to the Japanese governor of Kanagawa, and this led to several legal proceedings: a criminal case against Herrera for having illegally detained and punished his passengers, and two civil cases brought by the captain himself against the fugitives to force them to return on board. The Chinese indentured servants were freed by the Japanese authorities. Peru protested and, after a complex negotiation, the case was eventually referred by Japan and Peru to arbitration by the Czar of Russia, who decided the case in favour of Japan in 1875.

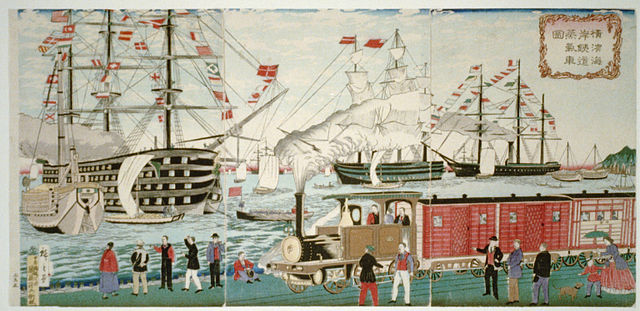

Dealing with foreign powers / Japan in Transition

The María Luz incident happened at one of the most important crossroads of Japanese history. The Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1868), which had ruled the country for more than 250 years, had come to an end, and the Meiji Era had begun. For approximately 230 years, the shogun had enforced an isolationist policy known as sakoku (“closed country”), when contacts with the outside world were kept to a minimum and strictly controlled. In 1853, under the American military pressure, Japan was forced to open its borders to international trade, and this, combined with internal factors, led to the collapse of the shogunate.The turbulent years of the bakumatsu (“end of the military government”, 1853–1868) had just ended, and the ruling elite of the new nation statewas busy dealing with foreign powers, building the political infrastructure of the new state, and pursuing reforms in many different sectors – all at the same time.1

- Auslin, Michael R. 2006. Negotiating with Imperialism: The Unequal Treaties and the Culture of Japanese Diplomacy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Howland, Douglas. 2002. Translating the West: Language and Political Reason in Nineteenth-Century Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ↩︎ - Kojima, Takeshi. 2004. Civil Procedure and ADR in Japan. Tokyo: Chuo University Press. ↩︎

- Kayaoǧlu, Turan. 2010. Legal Imperialism: Sovereignty and Extraterritoriality in Japan, the Ottoman Empire, and China. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ↩︎

In 1872 the modern Japanese legal system was still under construction, but at the same time the laws of the Edo period had mostly ceased to be in force: the result was endemic legal uncertainty. The ruling elite worked to conceal such uncertainty during the María Luz incident in their efforts to present Japan to the Western powers as a country fully capable of managing complex legal issues using tools and procedures that foreigners could relate to.

The “barometer of modernization”

The Meiji elite understood that demonstrating the mastery of the rule of law was fundamental to be seen on an equal footing to European countries. The law was a tool the foreigners seemed so good at using against Japan. Indeed, the opening of the country was obtained through the imposition of legal instruments:the Unequal Treaties. While of course reforms in the economy, military, etc., had a decisive impact on Japan’s accession to the club of international powers, the law had tremendous symbolic importance, and was indeed considered, in the words of Takeshi Kojima, one of Japan’s leading law scholars, the “barometer of modernization.” 2

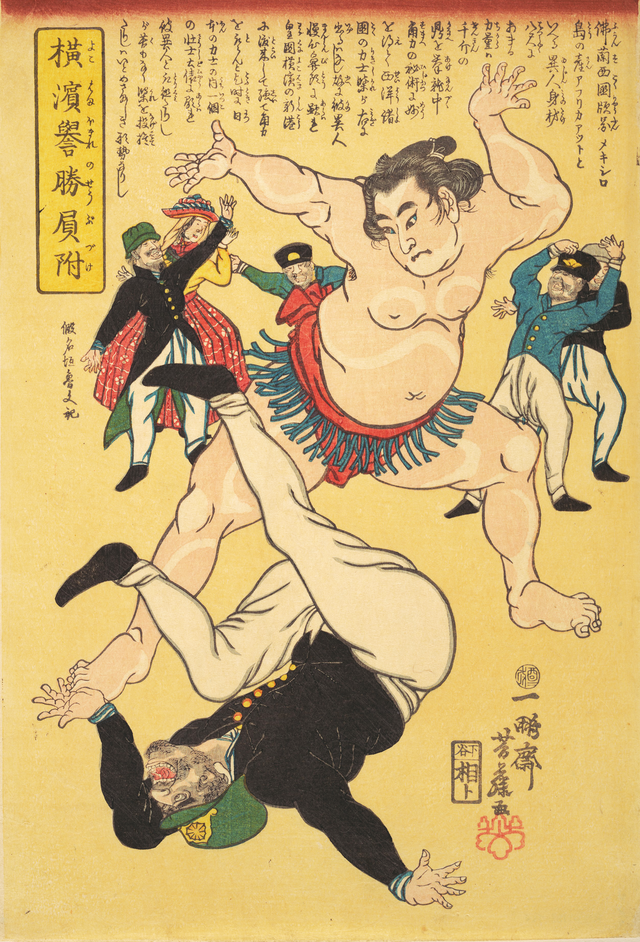

This is particularly significant for the status of Japan in the comity of nations. During this period of history, international law commentators embraced an imperialistic and colonial approach, and tried to establish a hierarchy of legal systems, which of course placed those of Europe and the Unites States at the top, and those of what were referred to as “uncivilized” territories at the bottom. Japan, together with other “Oriental” countries, was in an uncomfortable position as “semi-civilized.” 3

Europeans were skeptical that such countries could use international law as a tool of managing their external relationships at all. To be promoted to the upper league of “civilized” nations, Japan had to prove that its legal system, both domestic and international, was adequate from a European perspective. An important point to be stressed is that Western powers had no intention at all to reflect on the “barbaric” or backwards elements still present in their own legal systems, whether in homelands or colonies: the object of comparison was always an idealized Europe.

International Arbritration: Success but no Apology

The final prong of the María Luz incident, the arbitration in front of the Czar Alexander II of Russia, marks the debut of Japan on the scene of international dispute resolution. The Czar asserted with a final and binding award that Japan had complied with the principles of international law and that Peru was not entitled to any reparation. In this final stage, resorting to a technical legal procedure (i.e., arbitration) rather than seeking a diplomatic solution served the purpose of showing that Japan could act as a competent player in a proper international legal forum and use the tools of the law.

The Peruvian representative seemed somewhat irritated by the fact that Japan, an Asian nation, did not simply apologize and acknowledge the tort caused to a white man.

Before the decision to resort to arbitration, Peru and Japan engaged in negotiations in Tokyo: during these exchanges, the South American country relied on diplomatic pressure, and even resorted to some veiled threats. The Peruvian representative seemed to be slightly irritated by the fact that Japan, an Asian nation, did not simply apologize and acknowledge the tort made to a white man. The Japan-Peru controversy was indeed the first instance in which an Asian country invoked–successfully–the tools of international law to defend itself in the community of civilized nations.

Japan, together with other “Oriental” countries, was in the uncomfortable position of being seen as “semi-civilized”

The Legacy of the María Luz

The Japanese have not forgotten the María Luz. They still remember the case as a moment of glory for their country, in which they demonstrated their humanity and mastery of legal skills despite the difficulties the nation was facing in negotiating with Western powers. The case is even mentioned in policy papers today: a document written in support of Japan’s request for a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council specifically uses the María Luz example to show the longstanding engagement of the country with human rights and justice.